A Tower is Just a Tower

Our vertical legacy

Towers are often misinterpreted as the primary objective of the masterplans we design. In our recent proposal for the future of Brøndby Strand, the idea to re-establish the iconic skyline as part of the urban transformation unfortunately served as a focal point for various media. However, the ambition of the project has never been about the towers, but about reinvigorating the city fabric, the urban culture and the community of people living there.

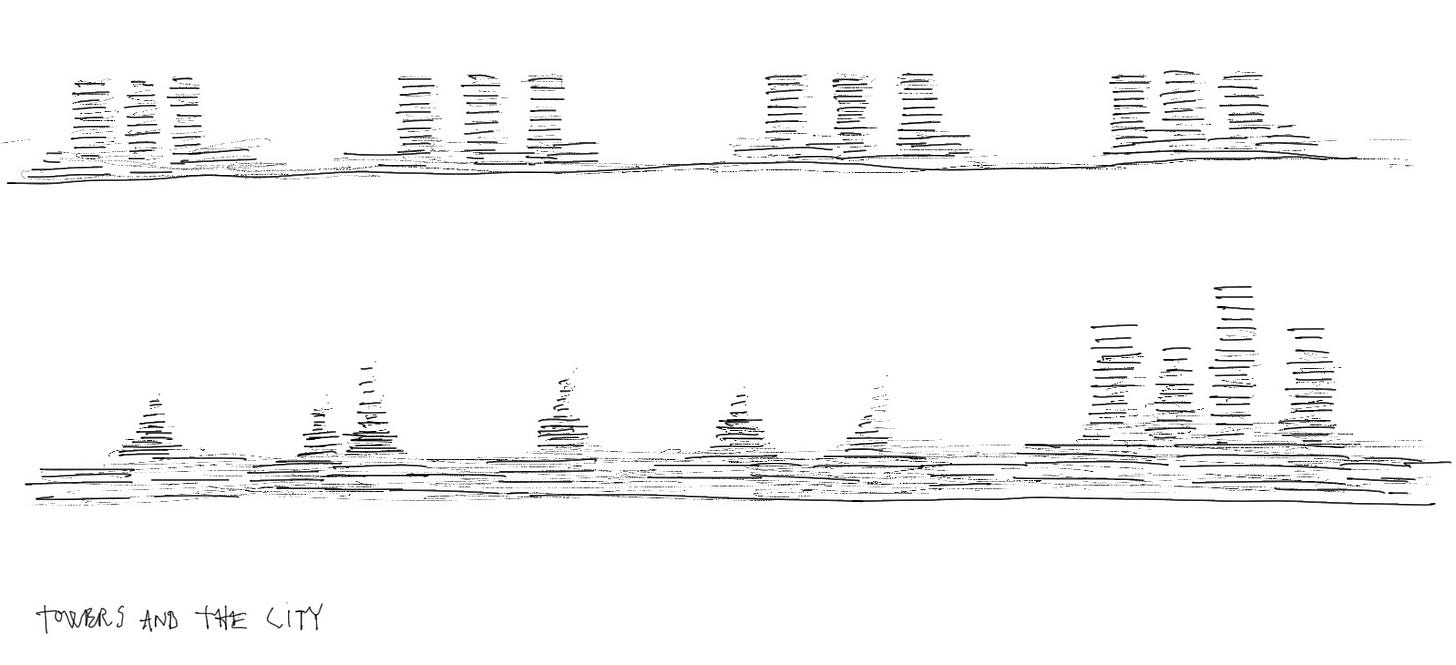

A tower is just a tower. Alone, it can be a very lonely and pointless mass of resources, reflecting a culture of invention and human desire to just go higher. A tower becomes more than just a tower when it is part of a whole, part of the city. Towers within urban contexts can be powerful and future-oriented structures, establishing an identity for a new urban area while providing the desired density or place of attention like a new node of mobility. Towers can frame an understanding of hierarchy and scale to the city when placed and integrated carefully. Though, it’s rarely the tower that creates the quality in the urban space, but instead relies on the built environment around to frame spaces for people to thrive within.

When we move around the city, well integrated towers seldom make us stop and look up, since we primarily experience the first 1-2 floors at street level, driving, biking or walking through the city. On the other hand, misplaced towers can ruin microclimates, destroy public space, and create lifeless urban spaces around them due to the wind turbulence and vast shadows they create. It is a complicated and delicate endeavor to integrate a tower into the city, especially in flat windy territories like Copenhagen. When we design and plan new urban neighborhoods today like at Brøndby Strand, the placement is thoroughly studied with advanced climate software to integrate with the spaces and densities around it.

Towers are visually impactful and fascinating from a distance when one observes the skyline or silhouette of a city. When they play the right role in the urban playbook, they can be part of explaining a narrative of historical and cultural values.

In modern Copenhagen you can clearly distinguish between the historical city of towers and spires from the 16th century, and the modern additions, such as the Arne Jacobsen hotel tower by the main train station, the cluster of new towers in the new Carlsberg neighborhood, or the renovated siloes in the north harbor district. Each area within the city deserves to tell its own story, with its own identity and strategy of creating vertical landmarks. Collectively they express the character of the city as a whole. Historically as well as culturally, towers are an important part of the urban narrative, and if successfully planned it proves a strong voice of city authorities and urban policies. On the contrary, it can also show the burden of a city run by developers, erecting whatever, wherever.

Towers of Brøndby Strand

The legendary towers of Brøndby Strand, were built as part of the 2 km long modernist structure, ‘Brøndby Strand Parkerne’, back in the early 70’ies. A development that represents an important part of Danish welfare urbanism, when families moved out of a worn down and unsanitary Copenhagen, and into the modern suburbs. Brøndby Strand represented a new modern life close to the beach with fresh air and recreation, with urban life elevated over the growing car park and infrastructural landscape. Modern housing units were built as a mix of apartment blocks, row houses and towers clad in white concrete and connected to Copenhagen within 20 minutes on the newly opened S-train line. The development represented a perfect new lifestyle, well portrayed in the documentary, ‘Fra Bondehus til Højhus’, with early residents and the architect, Svend Høgsbro.

This enormous and brave development represents an important part of larger Copenhagen urban expansion and history. It’s also one of the largest, most consistent, and iconic modernist neighborhoods in Denmark. With the 12 identical towers representing equality and social awareness, the development is a historical model of Danish welfare urbanism.

Today Brøndby Strand is a very mixed, but somehow divided community, between villa areas, apartment blocks, low dense clusters and finally the centerpiece of ‘Brøndby Strand Parkerne’. Culturally it’s also part of a broader movement, the contemporary hip hop culture of Vestegnen, a renewed integrity, for better or worse, commented here at the DR article ‘Rygtet om vestegenen’. The towers are an integral part of this modern culture, represented broadly as the iconic image of the place and its inhabitants, in music culture, movies and the rich and growing street art culture of the place. The towers are part of a whole, without meaning by themselves, but elevating the sense of place together. As the collective signature of the place, the towers represent the past and the future simultaneously, a colorful portrait of Danish urban history that requires respect and careful integration with the future ambitions of the area.

The towers being torn down due to toxic building materials are planned to be re-built as an integral part of the project for the future of Brøndby Strand. In the urban transformation we plan to keep the historical traces but re-think the structural logics of modernism such as traffic separations and monocultural planning which create problems of safety and comfort in the public space.

The project will bring connectivity between people, from building to building, from housing union to housing union, neighborhood to neighborhood and from city to nature with the coastline of Køge Bugt. The transformation will create a new sense of proximity, by redefining the traffic structure and remove large parts of the road ditches that separates people and neighborhoods today. The result will reframe the everyday life of the place and connect to a renewed town center and new public school, supplementing the culture house ‘Brønden’. Additional a transformation of Esplanadeparken, with improved and safe connections to the beach front will give shape to a range of new inclusive urban spaces in which to meet, both for the elderly, families and the young generations of the future.

A renewed relation between the twelve towers and the city will be part of a new social dimension of the place. The towers will continue to represent a clear and important urban signature, equal to the historical towers of Copenhagen, and part of the larger Copenhagen architectural DNA. Although, it will never be about the towers, but about the people and the urban culture around it.