Architecture for Now!

The collapse of chronology

All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist

- The Tralfamadorians, Slaugtherhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut 1969

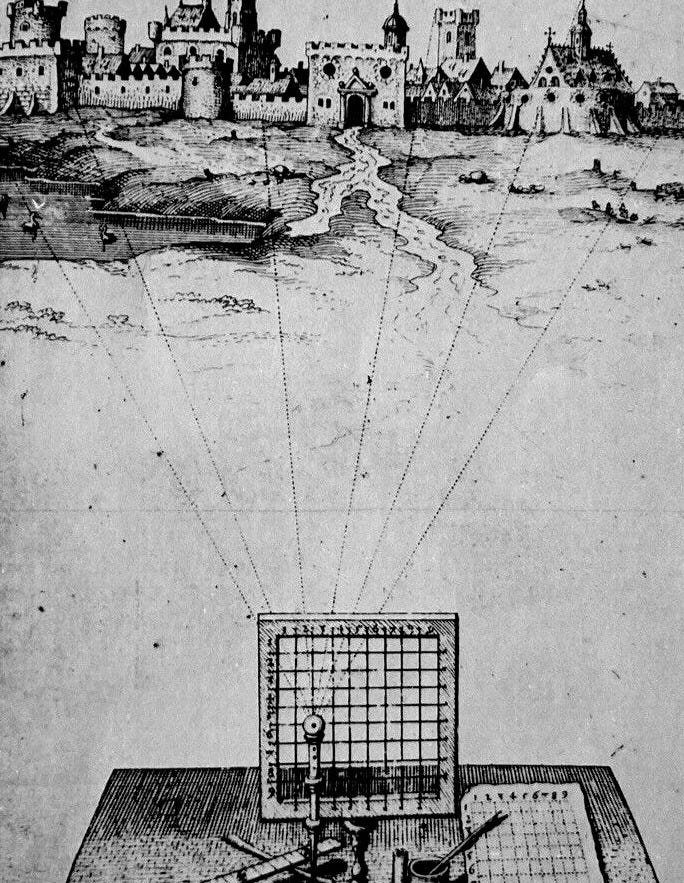

In the exhibition Preservation is overtaking Us, at Venice Architecture Biennale in 2010, Rem Koolhass spoke about a new paradigm in architecture, where chronology – a linear perception of time, cause and effect – seems to be collapsing. A situation where past, present and future is overlapping and becoming inseparable and flattened. Koolhass observes how since the first official preservation acts from around year 1800, the time interval between the present and the objects of preservation has moved from a 2000 year perspective to 200 year perspective in the revised act from year 1919, until the situation today, where construction is regarded worthy of preserving the minute it is completed.

We are living in an increasingly ‘historicized’ present.” Anything is potentially worthy of preservation: a concentration camp, a ruin, a factory, a freeway, a slum.

- Rem Koolhass

The past is overtaking the present, so to speak. Where Architecture was preserved for its ancient, religious, or cultural significance, we are no longer able to distance ourselves from what we create. What once had to stand the test of time is now preserved almost immediately. Time is no longer a real factor. There exists only the present moment.

There is only Now!.

When we speak of future-proof designs or of things that must stand the test of time, we speak of architecture that relates itself to chronology - past, present and future.

If we speak of Architecture for Now!, we disregard this urge to let our designs “live through time” as German thinker Eckhardt Tolle points out in his book “The Power of Now” .

When you are lost in time, when you live through time but not in the present moment, you feel a constant underlying anxiety. Psychological time is the mind-made dimension that contains your past and future and your identification with them. Psychological time creates the ego sense of self and the compulsive need to dwell in past and future.

In contrast to a chronological perception of time as a horizontal linear flow, the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard spoke of vertical time - punctuated experiences, and poetic moments.

Architecture for Now! changes our perception of architecture from being part of a horizontal time, to existing in vertical time. Architecture for Now! has a vertical relationship to chronology. It deals with matter - resources at hand - and with poetry - emotions related to experiences of moments caused by events and rituals in a place. Architecture for Now!, is unaware - indifferent - of its place in cultural history. But still, it has the power to transcend space and time. To become a portal into to personal history.

When Japanese fashion designer Yohij Yamamoto speaks of his designs, he acknowledges the fact, that fashion is fleeting and clothing is temporary objects. But the sensation of wearing his designs stays with you and changes you. Like German movie director Wim Wenders points out in Notebook on Cities and Clothes - his 1989 documentary about Yamamoto. Wearing the clothes - these fleeting objects - reminds Wenders of his father, and his childhood.

I bought a shirt and a jacket. You know the feeling; you put on new clothes, you look at yourself in the mirror, you’re content, excited about your new skin. But with this shirt and this jacket, it was different. From the beginning they were new and old at the same time. In the mirror I saw me, of course, only better; more me than before. And I had the strangest sensation that I was wearing... yes, I had no other words for it, I was wearing the shirt itself and the jacket itself. And in them I was myself. I felt protected like a knight in his armor. By what? By a shirt and a jacket? The label said, ‘Yohji Yamamoto’. Who was he? What secret had he discovered, this Yamamoto? A shape? A cut? A fabric? None of these explained what I felt. It came from further away... from deeper. This jacket reminded me of my childhood, and of my father

Architecture for Now!, is a shirt, a dress, a room you wear for a moment, that can have a profound effect on you, transport you and accumulate memories.

Architect Aldo Rossi (1931–1997), in The Architecture of the City, describes architecture as a repository of memory. Buildings, he argues, survive their functions. They accumulate meaning through time, becoming symbolic rather than merely useful. Buildings may not be culturally recognized; more often, they are deeply personal. A corner shop, a stairwell, a facade remembered from childhood may become one’s private Pantheon. Architecture for Now!, store personal memories, that live on after you, yourself have left. In this sense, Architecture for Now!, is also Architecture for Was and Architecture for Will Become - all at the same time.

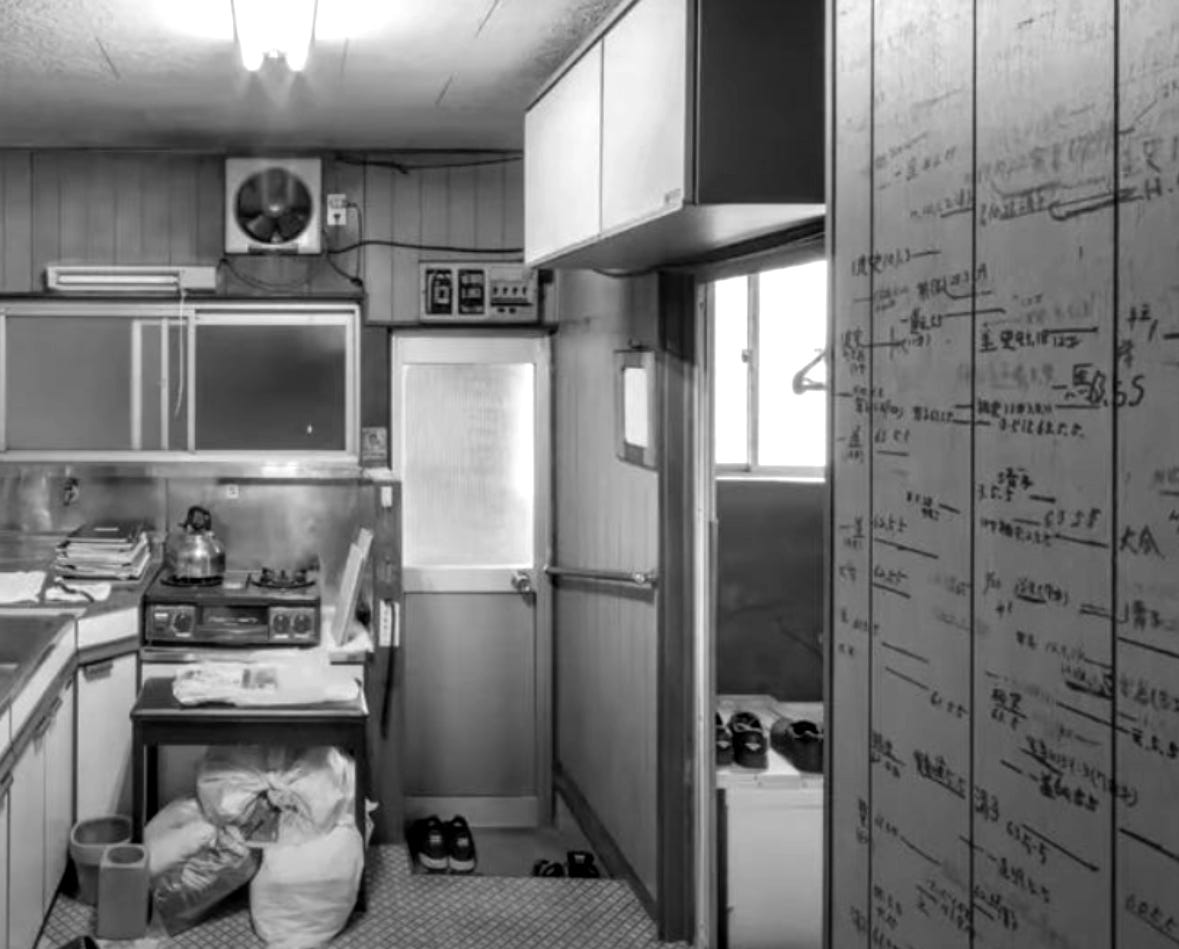

At the Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2021, architect Kozo Kadowaki exhibited the dismantled structure of a 1954 Tokyo townhouse relocated in Venice. The everyday markings left by a building’s former inhabitants—the documented heights of the family’s children in the kitchen—immediately transport us. These records of vertical moments in time—the act of noting a child’s height at that specific moment, in that specific kitchen, in that house in Tokyo—are instantly relatable to every parent who has done the same thing, across time and across the globe. Experiences that are tied to a place after we have moved on. Kadowaki said in an interview after working with the installation:

So maybe this house is not something I can own. It is a kind of common property that has passed through the hands of many people. Once we were awakened to this kind of feeling, you will see all buildings as common property of society

Architecture for Now!, is common property. It is part of society. It is triggers for recalling personal or collective memory.

In Search of Lost Time, by French writer Marcel Proust —a sudden, sensory-triggered moment, recreates vivid emotional experiences where the past floods the present. The starting point of the story arrives when the narrator, Marcel, dips a madeleine cake into a cup of lime-blossom tea. The taste unexpectedly summons a vivid, emotional recollection of his childhood. Time collapses: the past surges into the present. A cake - the madeleine - becomes a portal.

as soon as I had recognized the taste of the madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me… immediately the old grey house upon the street… rose up like the scenery of a theatre… and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I used to be sent before lunch, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine.

— In search of Lost Time, Marcel Proust

Architecture for Now!, is a portal. Places that trigger our senses. Our sensibility. Architecture for Now!, captures the fleeting and subjective state of the moment.

Throughout his career, Japanese film director Yasujirō Ozu sought to create a sense of weight in relation to the moment. In Ozu’s movies, scenes and dialogue unfold in Real-time, as opposed to the sped-up pacing we often take for granted in most films and television (the “Unreal” time?). Ozu’s slow pace give the moment a certain gravity—you feel the weight of reality, slowed down to the actual pace of life. Ozu’s movies are on the surface utterly uneventful. As uneventful as most peoples lives. Camera angles flat, fixed and low to create a sense of objectivity. Stories unfold slowly in common places. The stories unfold between the walls of Architecture for Now!.

Real-time is the time of the moment. Still, Real-time can transcend time and space. A vertical moment can feel like a life time.

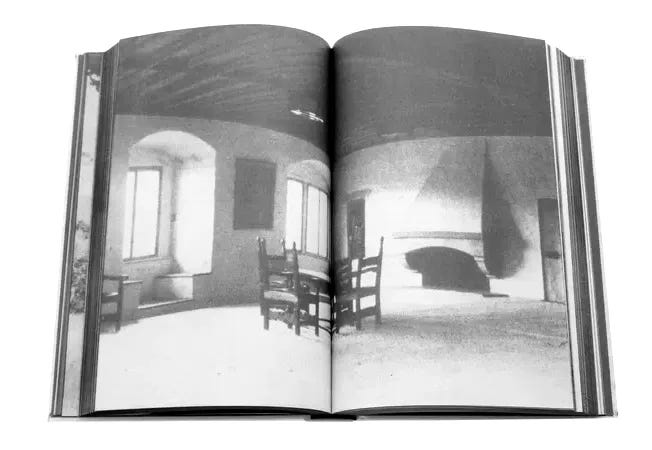

Set within the marvelous walls of the Winter Palace - the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg - the film Russian Ark by Russian film director Alexander Sokurov, is shot in one continuous 87-minute take, set during a grand Russian ball in 1913. As the camera glides through 33 different rooms, you encounter figures and scenes spanning from Peter the Great’s 18th-century rule up to the pre–World War I era —just before the seismic changes of World War I and the Russian Revolution.

In essence, although shot in Real-time - a moment in time - its narrative transcends historical chronology—portraying an “eternal present” that interweaves centuries of Russia’s past within the museum’s walls. The contrast between the time‑blending journey through roughly 300 years of Russian history and Real-time creates a feeling of chance and potential in the moment. Everything can happen. The moment can change the course of history. In Russian Ark, Real-time feels accelerated, charged with possibility.

Architecture for Now!, is architecture for Real-Time, not Architecture for an imagined future. Not Architecture for Later.

In his film Fitzcarraldo, German director Werner Herzog tells the story of a man who dreams of building an opera house deep in the Amazon jungle. A monument to Western high culture imagined in the middle of the wild nature and among native peoples. Fitzcarraldo is obsessed with greatness. With legacy. He wants to build Architecture for Later - not Architecture for Now!

To realize his dream, Fitzcarraldo travels the Amazon River by steamboat, only to encounter a monumental obstacle: a mountain blocking the path of both the boat and his vision. This leads to a herculean effort to haul the massive steamboat over the mountain—an achievement that is long and grueling.

This extreme consequence of one mans unwavering vision embodies the physical struggle and pain of a task performed by hundreds of enslaved native workers, creating a sensation that time itself is decelerated into an unbearable moment that feels like it will never end.

Human sacrifice and time become the values by which we measure monumental (even if Sisyphean) endeavors and achievements of Architecture for Later.

In the same way, we assign enormous cultural value to monumental efforts like the construction of the pyramids —not so much because of the timeless beauty of their design, but because of the immense effort and human sacrifice we imagine was required for their construction and completion. The pyramids is not Architecture for Now!

The absurdity of carrying a steamboat across a mountain underlines the contrast between different perceptions of time - the horizontal and the vertical. For the human beings carrying the ship, the present moment might feel like an eternity, but for the mountain, it means nothing. Fitzcarraldo’s vision is grand yet vain and fragile; nature and time will eventually reclaim everything. In the context of nature, human achievements feel fleeting and temporary. Architecture for Now!, is indifferent to this. Architecture for Now! does not wish to compete with nature.

In the writings of German natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt, he wonders about the slow processes of nature, geology, evolution, and climate—reminding readers how brief human lifespans are in the vast expanse of cosmic history. This shows how nature remembers what humans forget.

When, in the solitude of the Cordilleras, at the foot of the lofty palm-trees which skirt the cataracts of the great rivers, we listen to the noise of the torrents, and gaze on the starry vault of heaven, time seems to vanish, and we are transported beyond the limits of our own age and nation.

Days passed like moments, and yet every hour was filled with a thousand images. The senses, overburdened by the multiplicity of impressions, made the passage of time imperceptible.

— Alexander Von Humboldt

It is in the presence of the eternal—the vastness of what feels like forever to the human mind—that we experience the moment as profoundly present. This captures how immersion in nature suspends ordinary time, evoking a timeless, near-mystical state. A sense of presence that is, on one hand, accentuated by time in terms of scale, but also in terms of stimulation.

There is a timeless way of building. It is thousands of years old, and the same today as it has always been.

— Christopher Alexander

American architect and writer Christopher Alexander describes his search for this near-mystical timelessness (a quality without a name) in The Timeless Way of Building. For Alexander, timelessness is not about resisting time, but about building in a way that aligns with the deep rhythms of human life. Build for evolution, in the way that nature does. He studies the patterns of human lives and formulates a “pattern language”. A generative and participatory design philosophy, encouraging buildings to grow organically, in pieces, like living organisms. The goal is not an immortal structure, but one that evolves in harmony with its inhabitants. Time becomes a design material, a tool to shape spaces that live. Architecture for Now!, is not a static object, but architecture for evolving moments and changing needs. Architecture for Now!, is built for necessity.

When Koolhass in a 2008 lecture at Columbia University, said:

Thirty years ago architecture was a very serious effort, using workers and presumably producing buildings that were not luxury items, but necessary. And therefore, not necessarily committed to immediate or obvious beauty but, in a genuine way, much more interested in doing what was necessary. I think that architecture is gone

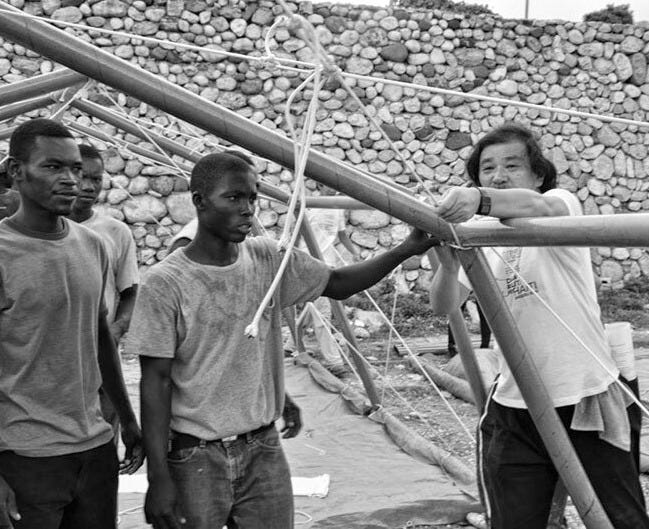

Then; Architecture for Now!, is the antidote of this. It relates itself to relevance, significance and urgency. Architecture for Now!, is when Japanese architect Shigeru Ban builds temporary emergency homes from temporary fleeting paper materials.

The beauty is neither immediate nor obvious; it is trivial. Like in literature, it is through the presence of the universal in the trivial that we experience Architecture for Now!. It is through experience which cannot be rendered objectively. Architecture for Now! resists measurement and data. It is not documented so much as illustrated, narrated, and felt. What endures is not the record, but the retelling. Narrative is the vessel. A constructed, selective, and subjective form through which we understand ourselves and the world. Architecture for Now!, is built from stories—individual and collective—and it is through these that we transmit experience of the Architecture for Now!.

In Invisible Cities by Italian writer Italo Calvino, the world itself becomes a projection of memory and desire told through stories. When Marco Polo relays his experiences from visiting exotic places in the world to the listener Kublai Khan, the cities are not physical locations so much as states of mind—distillations of emotions, senses, thought, and longing. Cities, in Calvino’s rendering, do not unfold their history; they embody it. In the city of Zaira, the past is not told but “contained like the lines of a hand.” In Zobeide, the city becomes a distorted recollection, built from dreams remembered differently by each of its inhabitants. There is no original city—only its recurring image, refracted through longing. The physical becomes diluted. The factual, unstable. The Invisible Cities do not concern themselves with objective reality. They exist only as manifestations of the subjective narrative told from one human to another. Do we need any other reality?

Architecture for Now! 2025