Restoring Meaning

Through 'Energy Landscapes' renewable energy production can act as leap towards resilient rural and cultural landscapes - restoring the 'lost meaning' of the open land.

‘Energy landscapes’ are the next leap in the transition from fossil fuels to renewables. Their future presence and size will increase significantly - resulting in local community paradoxes and ecological compromise. This text conveys the potential of how these anthropogenic landscapes, through holistic nature based design, can create better environmental impact and restore the ‘lost meaning’ of the cultural landscape we and other species inhabit.

Overlooked potentials

Cultural landscapes are ever-evolving. They transform and continue to do so. In the face of current ‘polycrises’—climate change due to global warming, biodiversity in decline and the social quest to restore a 'lost meaning' through this transition—the cultural landscapes we inhabit are subject to another indisputable transformation. The development of emerging renewable energy plants or ‘energy landscapes’, must due to the sheer scale of it, be met with an holistic approach, we as landscape architects possess a liability to grasp.

In June 2024 the Danish government pointed out 12.000 ha of open land, which are to be transformed into ‘energy parks’. Wind and solar farms will hence get larger presence in future landscapes - making renewables more comprehensive for local communities and environments. But isn’t there something we overlooked? Is it possible through a solid landscape understanding to on one hand regain local support, meanwhile strengthen habitats for wildlife, recreational routes for humans and restore the lost meaning in cultural landscapes?

Who’s landscape?

The ongoing transition from fossil fuels to renewables, contains potentials to restore lost qualities, which was synonymous with ‘open land’ prior to the centralization of late modernity. Qualities that linger in the relation between human beings and nature and can be introduced as carrying design drivers - qualities like recreation, mediation and immersion. To reestablish the negligible lost connection between humans and the naturals - giving people a possibility to regain their aforementioned confidentiality with their ‘place’, these topics must be introduced as design drivers for future cultural landscapes.

The scale of renewable energy plants have increased significantly since pre-industrialism, not only in terms of the amount produced but also the size of the infrastructure. Along with the growth in scale, ownership centralized. In the pre-industrial era, water mills—owned by the steward of a property with a creek flowing with kinetic energy—produced limited amounts of mechanical energy, serving specific needs for daily life on that particular property. The social and economic impact was immediate, creating a tangible point of connection for the community. In contrast, modern wind and solar farms, which generate large amounts of electricity for export and are managed by large corporations, often have little impact on the local environment beyond their vast physical presence. This detachment reduces the sense of "meaning" and creates challenges within local communities. Another point of detachment is the incorporation of roadside paths, living fences, and water bodies into agricultural production, displacing wildlife and declining colonizing vegetation. This evolution has left most of 'open land' as space that is no longer accessible to inhabitants besides farmers. These detachments create problematic paradoxes, like the 'Not in My Backyard' (NIMBY) syndrome. An obstacle is citizens' concerns regarding the consequences of renewables, but who are to blame them? As globals, we acknowledge the need for renewables, but as locals we would rather prefer them at a significant distance from us.

Therefore, it is important that the planning and design of renewable plants involve a thorough consideration of the landscape architectural expression and natural features that promote local qualities, enhance biodiversity, and strengthen ecological dynamics and networks. By taking into account existing narratives and conducting a comprehensive landscape analysis, the local community can regain the lost sense of belonging to the cultivated landscape and find meaning in the existence of energy landscapes.

Give soil a chance!

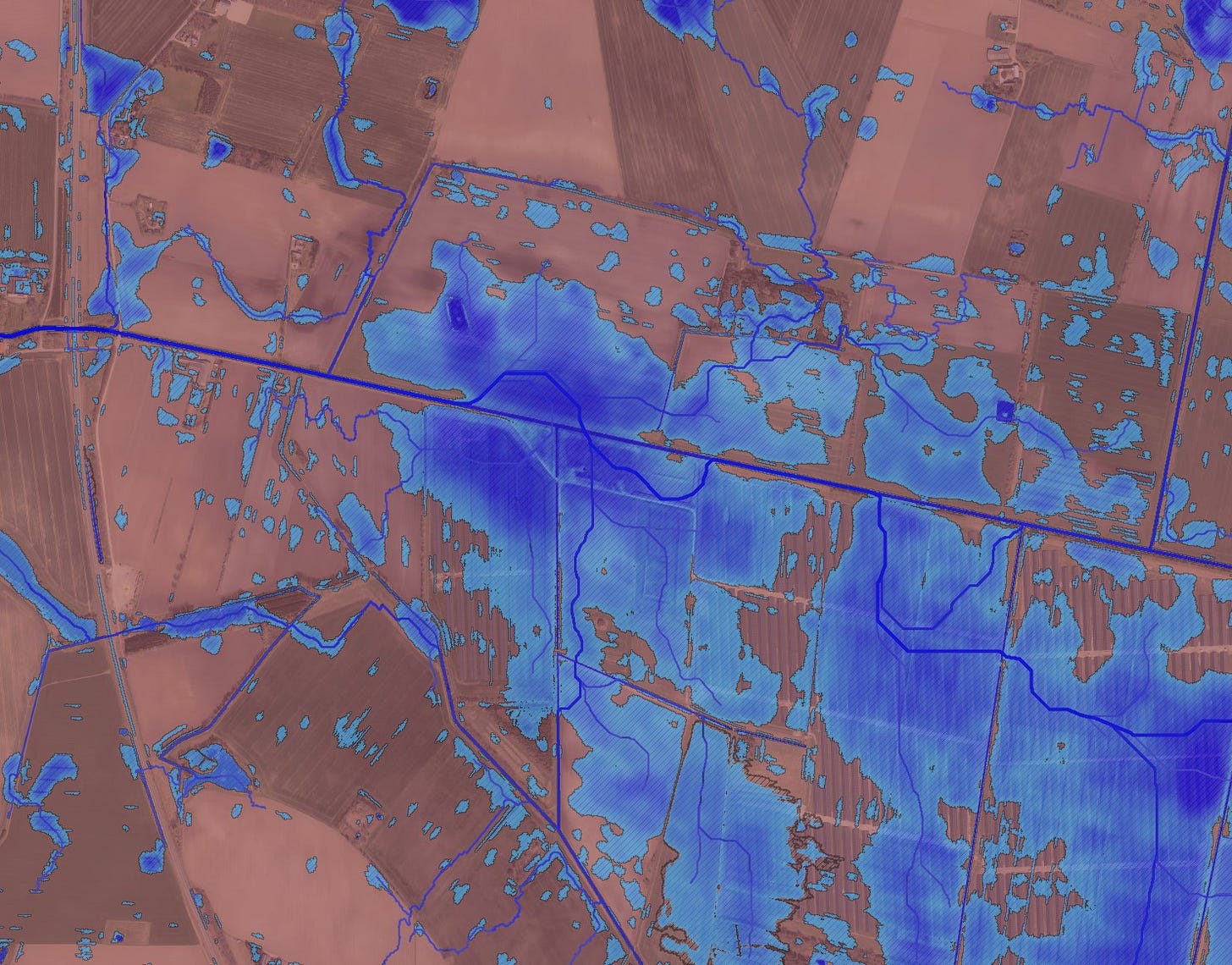

As a specific approach, whether it involves solar parks, charging stations, or other technical facilities, the primary focus must be on strengthening natural and ecological connections that exist within and around a project area. By analyzing features as water conditions, a solid foundation can be established for the placement of technical elements such as solar panels. Existing waterways can be enhanced through minor terrain adjustments that optimize flows and allow certain areas to remain dry. Low-lying land that submerges during winter can be incorporated into the planning process, strengthening habitats by removing them from production and leaving them untouched. In general, the natural types within project areas should be able to function without significant intervention, as the operations are designed to support and strengthen nature's own dynamics.

We must aim to implement nature-based maintenance, which aims to mimic natural processes. Nature-based maintenance is a way to create holistic caretaking of a given landscape, enhancing natural potential and biodiversity. In this approach, we focus on the health and well-being of vegetation and habitats, allowing nature to perform its functions. Once a landscape analysis is completed, it becomes possible to design nature-based maintenance that also integrates and engages the local community into the process. This can be achieved through activities such as collective annual haymaking, seed collection, or foraging.

When establishing solar parks, a central point that has a large effect on the vitality of flora and fauna, is the time break that the farmed soil gets from circulation. The frequency of plowing, turning, seeding and harvesting makes it impossible for the soil to establish a balanced nutritious flora, where microbes and smaller animals keep the soil airy and alive. The soil is alive, but it needs rest to live. A healthy soil with good biodiverse potentials, is what the result will be, if we just give soil a chance.

A Unified Whole

Creating awareness around natural dynamics—mediation that fosters a sense of ownership—is crucial for generating a collective effort towards the green transition. Many people still feel disconnected from the polycrisis (the climate, ecological, and biodiversity crises)—that is, what does this mean to me? The dissemination of knowledge of the specific landscape we live in plays a significant role here. It must be communicated in a way that allows you to experience it physically—not just read about it on a screen or in your preferred media, but embark on a journey of discovery that provides an overview and captivates you.

We are facing the largest transformation of our cultural landscape since the Danish land reforms of 1780, not only due to ongoing plans for energy parks but also because of the transformation of agricultural land into natural landscapes. Denmark’s new ‘Green Tripartite’ aims to increase forest areas, impose a CO2 tax on agricultural emissions, remove low-lying land from production, and restore ecological balance in Denmark’s desolate seas. The 12,145 hectares of planned energy parks cover 0.3% of Denmark’s area, and 400,000 hectares of agricultural land will be converted into forests, nature reserves and wetlands, which amounts to 10% of Denmark's total land area. We should not view energy landscapes as an isolated part. Instead, they should be seen as part of an integrated whole, where renewables, nature restoration, and climate adaptation are all interconnected. This transformation calls for a coherent unified approach that collects perspectives of both ecological and social potentials. This to establish a solid foundation for a future balanced landscape transformation that works on a high ecocentric level. How? By giving the land back to its people and other species.