Time Matters

Projects are never truly finished on the day we hand them over. They are living stories—always in motion, always becoming, always carrying the past forward.

Architecture is bound to time, not just because buildings age and decay, but because they exist in motion, between what once was and what has yet to come. Transformation makes this motion visible. We inherit buildings, structures, and layers shaped by past generations. We adapt them to today’s needs. In doing so, architecture remains relevant, and buildings live longer.

But we must be careful not to lose ourselves in the moment, designing for permanence alone. Buildings that appear as finished, untouchable pieces of architecture the very day they are completed. Objects to which nothing can be added, and from which nothing can be taken away. But the truth is, as David Leatherbarrow reminds us: from the very first hour a building is inhabited, change has already begun.

He reminds us that these changes are, in reality, quite trivial. First scratches on the floor and marks on the walls. Next, painting and rearranging of furniture takes place. This leads to the addition of new partitions, as well as the installation of new doors and windows. Later, more of the original structure is removed, and new elements are added. The sequence of changes only ends the day the building is demolished - but even then, traces can continue to be embedded in our memory1. Traces and memories of what once was. Echoes we may not carry alone, but together, shared with others.

As architects, we must therefore work with time as an ally. We build upon works created long before us, and one day others will build upon what we have created. It is not about denying our desire for permanence. Materials still need to be durable, repairable, able to patinate with beauty, and enter new cycles. But it is about rethinking the question: When is a project actually finished?

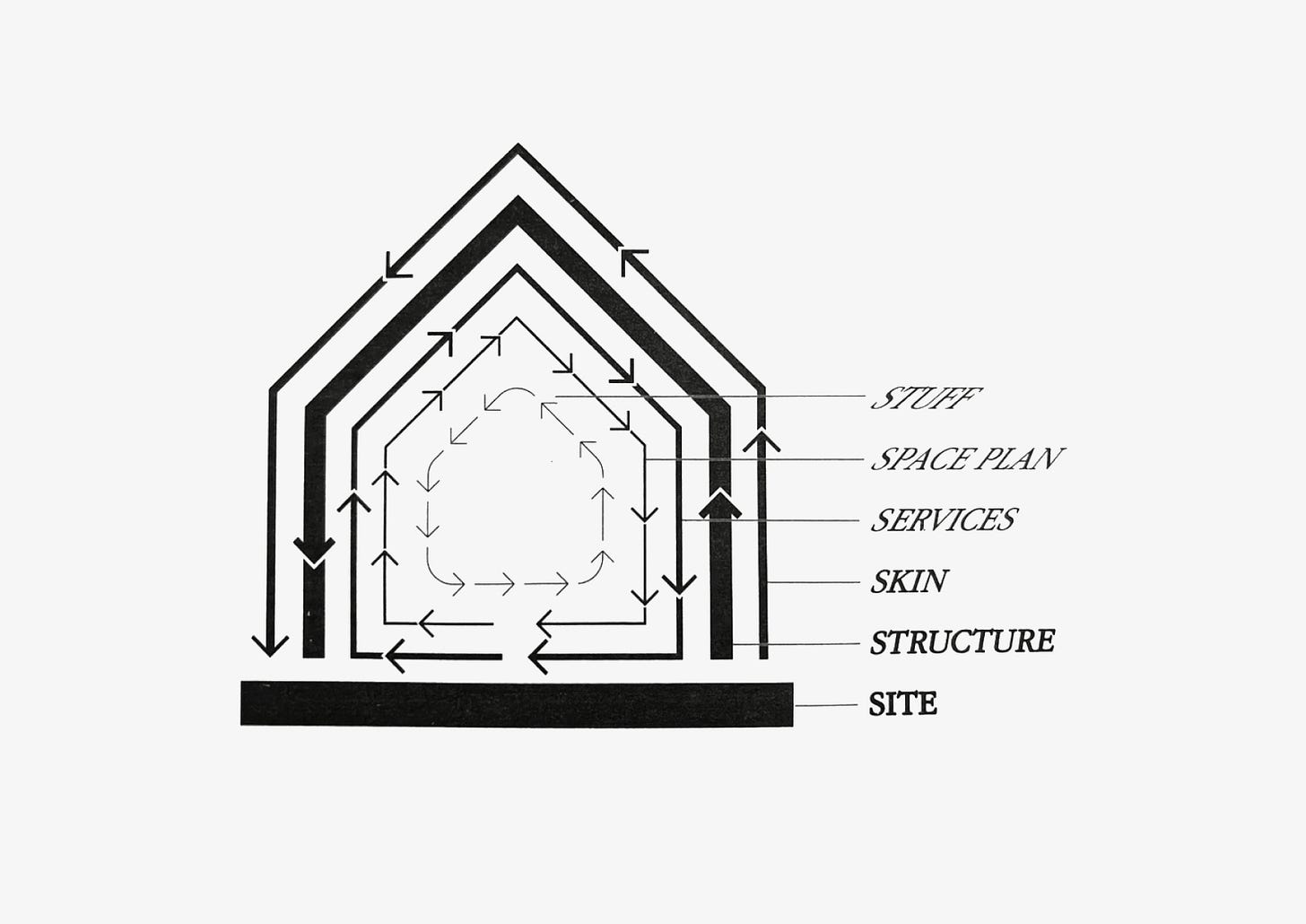

In How Buildings Learn, Stewart Brand explores what happens to buildings after they are built. What occurs when users take over, adapting the architecture to meet new needs? The challenge is: Most buildings are not designed to adapt, but they do it anyway. Brand’s concept of Shearing Layers offers a lens to understand buildings as time-bound layers: site, structure, skin, services, space plan, and stuff, each with its own lifespan. When these layers maintain a degree of independence, they do not block each other. Buildings can adapt, evolve, and endure. Over time, these adaptations give architecture character, leaving marks of lived experience2.

Like great cities that grow over time, constantly becoming without forgetting their past, we can weave our work into the architecture that already exists, adding depth to the story. Buildings make places recognizable, and by allowing the existing to remain a part of the future, we strengthen the collective memory we share with others and nurture a sense of belonging.

Buildings from the past must serve the present and stay relevant for the future. When we transform them, we stand on the shoulders of generations before us, and the traces we leave will mark the path for those who come after. Projects are never truly finished on the day we hand them over. They are living stories—always in motion, always becoming, always carrying the past forward.

Leatherbarrow, David. (2021) Building Time: Architecture, event and experience.

Brand, Stewart. (1994) How Buildings Learn: What happens after they’re built.